在我前的你們

YOU BEFORE ME

A multimedia project documenting a story in my family history and collecting thoughts about what this means to me.

Derek Ng

My immediate reaction when my parents told me about the CDs was convincing them they should burn it onto a computer, get a soft copy. Though I’m no tech junkie, I’m a romantic enough to know that CDs, like all things, have their expiry dates. (Or perhaps it could be that, in who knows how long, we’ll no longer have machines that can read CDs.) I pleaded with them endlessly to put the three-hour wedding video anywhere else—a USB, a drive anywhere in the ether. At first they were hesitant—this is another one of Derek’s nonsensical ideas, they must have thought—but then, after my insistence persisted, my mother exchanged one of those looks with my father, and they relented. A week later, my father got back home from work and wagged a USB stick proudly before me. He had asked one of his younger colleagues at work to teach him how to store the videos securely on a thumb drive.

I wanted a copy, I said. Sure, he replied.

So that’s how I ended up with three hour-long videos of my parents’ wedding on my laptop. They are stored in a folder titled “LOVE,” along with other precious photos of friends and family I’ve saved over the years. While the quality of these videos isn’t amazing, they are somehow one of the most important things in my possession. On my more homesick days in New York, I click open one of the videos and forward myself to a random moment. I watch the videos in tremulous anticipation, letting myself get swept up into this other world: the excitement of the happy day, the interested chatter, the shaky camera work. It’s almost like I’m back with them on the special day of their marriage—not just in Hong Kong, but also in 1999, two years before I was born.

When I watch these videos I find myself in a strange place in my mind. I am so intensely curious about the tapes, so excited to recognize the people that I know, that I feel almost like I am a ghost, a specter transported across time and space to be with his relatives and ancestors. Wasn’t it just yesterday that I was with Babi when he knocked down the doors at Cheung Ling to greet my mother and swoop her away on the wedding sedan? Yesterday that I sat next to Mami as she had golden bracelets clasped onto her wrists? A wallflower in these happy memories, I pretend like I was there right beside my parents, even if I understand how ridiculous this fantasy of mine is. (These are not my videos. This is not my time. Even identifying these people by the names I know them—Babi, Mami—is an anachronism in itself, because in these videos they are still newlyweds, for whom the thought of children hadn’t even in come into the picture.)

What is a child’s relationship to the stories of his parents?

What is my relationship to memories that aren’t mine?

These are the questions that have drifted across my mind as I’ve pondered my relationship to these tapes. As I have reflected on these videos—both alone while assembling this project, and also across extensive conversation with my parents as I’ve watched the videos with them over Zoom—I am coming to understand that these questions hint at what being a son means: not only being the successor of your parents, but also of their memories, even though they predate your very existence.

As I grapple with my role as a son, a writer—a, dare I say, budding essayist?—it occurs to me how important it is, to me, that I not only preserve and document these memories I am inheriting, but also, in the process, begin to understand what they might reveal to me about myself.

Scroll to: “Now That I Have You,” the song my parents chose to commemorate their special day—and the song that looped continually in my head as I arranged this project.

MORNING

SOUTH HORIZONS

The day’s festivities kick off with a congregation of bridesmen under an overcast sky.

As I consider the events, I can think of only my father who’d be able to pull off an event as extravagant and demanding as this. Part of what I, an anxious, overly-concerned person, have always admired in my father is his confidence in doing his own thing. It must have been this unwavering spirit that led him to bring his friends together on January 1, 1999, monopolizing the schedules of every member of his social circle—his posse of friends gathered from his middle school, St. Paul’s Boys’ College, and his hall in college, Ricci of Hong Kong University. At six o’clock of this drizzly morning, he gathered them all—drowsy but excited—at the lobby of his residential complex, South Horizons, and began the ceremony that a large wedding like this necessarily demands.

Below, you’ll find the commentary my parents gave about the videos as we watched them together. We communicated mostly in Cantonese, with English sprinkled occasionally within. Where necessary, I’ve provided my own translations in gray text.

Babi: 嗰朝呢就好早㗎 … 我哋嗰日好驚㗎,你睇吓個天,唔好落雨,但係唔好天嘅。

I was so scared that morning. Look at the sky. It wasn’t raining, but it definitely wasn’t a good day.

Derek: 咁最後有冇落雨?

Well, did it rain in the end?

B: Wai, no, 但係我哋我好驚㗎嘛。

Well, no, but we were scared!

Perhaps I feel so connected to these events because I’ve seen, and lived in, every one of these places. For the first ten or so years of my life, for instance, I lived in South Horizons. Every morning in elementary school, I’d wait here with my dad for the schoolbus to come pick me up.

B: 你睇吓呢架車。呢架 Benz 呢,係 Yaddy 俾我哋嘅,因為我哋嗰時冇車。呢架車係嗰時最靚嘅魔道嚟嘅。好貴㗎。

Look at this car. It was a Benz, lent to us by Yaddy (my dad’s old boss), because we didn’t have a car back then. It was the newest model back then, super valuable.

B: 我哋 Chinese 有個 custom 㗎嘛:任何人幫你做嘢,你都要備份利是佢。咁我哋嗰日司機,差唔多到 lunchtime 嗰時,就同阿Jose講:“Kenneth頭先俾咗封利是我,係諗住想點㗎?係一份意思,定係留咗,定係咩?

We Chinese people have a custom, right: Whenever someone helps you do something, you’ve got to give a red packet to them. Well, our driver that day, when it was around lunchtime, asked Jose: “So, that red packet Kenneth (my dad) just gave me—I wonder what he was thinking? Was it just a symbolic act, or did he really forget to put money in it?

B: 因為我頭先俾咗封利是佢,入邊就冇嘢嘅。就係等於話新年快樂,我俾封利是你 — a red packet, but nothing inside.

Because the red packet I gave him was blank. Like giving someone a red packet at Chinese New Year, but with no money inside.

D: Well, did you give him any in the end?

B: 咁咪Jose同我講,我就即刻插返啲錢入去。

Well, after Jose told me this story, I was so embarrassed I immediately stuffed money into his packet.

B: 咁大班人一齊嚟啦,通常好少嘅。因為 Chinese tradition 你班兄弟係好少嘅,我哋仲要而家有10幾個,同埋我哋而家着緊呢啲 Chinese 衫,嗰時好少有人着嘅。我哋真係好威,in the sense that it was such a big thing.

It was rare to see gatherings of so many people, because, in Chinese tradition, you usually hang around a smaller group of friends. Here we had over ten people, and I was in traditional Chinese garb, which few people did at the time. I thought we must have looked really smooth, especially in the sense of us doing such a big thing.

D: 你哋全部都好後生.

You guys all look so young.

B: 係咪好有型呢?

Don’t we all look so cool?

D: 睇吓Uncle Lau.

Look at Uncle Lau.

B: 嘩,阿強啊,阿成呀,你個契爺。睇吓,佢哋全部幾後生。你睇吓阿奇啊,咁多頭髮。

Wow, and Ah-Keung, and Ah-Sing, and your godfather. Look at them. They’re all so young. Look at how much hair Ah-Kei had.

B: And also Lena, the only woman on my team of my brothers from St. Paul’s Boys.

D: From St. Paul’s Boys?

B: St. Paul’s Boys 嗰時 matriculate 女人嘅。

At that point, St. Paul’s Boys already began to matriculate women, too.

D: 租定買㗎,呢啲衫?

Were you renting or buying these clothes?

B: 全部租㗎,你着得一次你點解會買呢?但係,你睇吓呢啲鞋,我哋新買嘅。你睇吓啲質地,全部發光嘅,好靚㗎。

Of course we were renting them. Why would you buy it for a one-off occasion? But, look at my shoes—those were new. The quality of them, they were so shiny, so pretty.

B: 睇吓呢個 fabrics 寫咗啲咩?“吳府迎親.”

And look at what those fabrics are saying: “The Ng Family welcomes its kin.”

D: 你自己造㗎,呢啲?

Did you make these sashes yourself?

B: 唔係,Jose 同 Katherine自己逐條逐條幫我整㗎,我好friend嘅,嗰時同佢哋。

No, Jose and Katherine sewed these one by one for me. I was really close friends with them at that time.

Ah-Kei, my dad’s childhood friend

Lena!

The customary sashes

B: 睇吓,睇吓我哋幾威!

Look at how suave we were then!

B: 嘩,你睇吓隔離嗰啲人,嚇死人呀!我哋幾大班人?

Wow, look at the people around us. We were probably scaring them so much, with how big of a group we were.

B: 個個都怕曬我,得我一個自己威。好似打交咁。

Everyone was putting up with me that day. I was the only one who thought we were so cool. To someone else, it could almost have looked like we were squaring up for a fight.

B: 幾尷尬呀,你睇吓King Kong個樣。It’s all about me and my idea.

Haha, they were so embarrassed. Look at how unamused “King Kong” (nickname of my dad’s friend) looks. It was all about my and my ideas.

D: 咁你嗰日結婚,你大晒啦。

Well, it was your wedding that day. You call the shots.

B: 你睇吓,我嗌佢哋舉起手指公。

Look, I’m even asking them to raise their thumbs and pose.

D: 你性格,一啲都冇變。

Your personality hasn’t changed one bit.

B: Haha, everyone is so reluctant, see?!

digression 1: a form for image and word

Arrangement of photo and words as a mode of essayism

Pondering the form of my project to-be, I start at the bedrock of bell hooks’s “In Our Glory: Photography and Black Life.” She writes extensively, and helpfully, on how images inform Black identity. They not only act as a way for Black communities to reflect on the storied memories passed on through generations, but they act also as a reflexive space for Black communities to reclaim identity away from white supremacist gazes.

What I find so important, especially as one working with a set of videos, is that hooks makes clear how images inform and shape our identities, holding in themselves deep meaning. That is, images serve “to sustain and affirm memory” (63), to bolster the pasts that we lay claim to and call our own. For that is the goal of my project: To let the images breathe life into these memories, and to draw meaning about myself from this process. I know, in part, that I must find a way to let these images sit.

hooks also allows for the possibility of words, carefully chosen, to augment the meaning of images alone: “When words entered,” she writes, “they did so in order to make the images live” (63).

So I tell myself: As the images themselves imbue my project with rich meaning, there is also opportunity to locate the right words to complement my images. Words, I realize, not only authored by me, but taken also from the conversations I must have with my parents.

Should I create a blog post? I am drawn to the idea of a living, breathing online repository that ties together all aspects of my thinking.

The form is right for my purposes, I think.

It will let me arrange the images in relation to one another, to trace the narrative of that one day in 1999.

It will let me play the videos in all their glory. The music, the conversation.

It will let me impose the narration of my parents above it. To incorporate their gracious input, transcribed after the many weekend hours they spent calling me from the and watching these videos again with me on Zoom. To creating a new, living, oral archive of their experience—explicitly on the page, “making connections between past and present” (63), in hooks’s words.

EARLY AFTERNOON

CHEUNG LING

As per Chinese customs, Babi travels from his neighborhood to Mami’s to “pick her up.”

Generally, my parents are liberal people. But, when it comes to certain things, like their wedding day, they are devout followers of Chinese tradition.

So, as the day continued, they corralled their families and friends into organizing and participating in all the requisite activities: not only the banquet, to come later at night, but also the traditions that would underlie a Chinese wedding in the late ’90s (some downright absurd, others tenderly serious).

After the excited gathering of brothers at South Horizons, my dad and his bridesmen packed into cars and a busy schoolbus—exactly the kind I’d take to school when I was younger—and drove the forty-five minutes to my mom’s neighborhood, Cheung Ling, on the other side of Hong Kong, where, as custom dictated, my dad would “pick up” my mother.

Babi rode in the car alone …

… while his bridesgrooms were crammed into a bus. Almost like it was school again.

Here they are, lined up all at the lobby of Mami’s apartment complex, ready to go “pick her up.”

At the moments I feel sad I wasn’t around for this, I am also comforted by the fact that my dad’s personality hasn’t changed one bit.

B: Everyone is 尷尬, only I’m not.

Everyone’s so embarrassed. Only I’m not.

M: 好雨㗎嘛,你哋喺條街度。

Well, of course—you guys are on the streets.

B: Babi揸緊嗰束花都好似係Mami整架,你睇吓幾靚!

But look at the bouquet I’m holding. [To me] I think your mother made that for me. Isn’t it so pretty?

Jittery, excited, and all dressed up, the guys tore through the streets leading up to her complex playing games, dancing, chatting, taking pictures like they were celebrities. (Or perhaps it was just my dad, while his brothers smiled politely). On the other end of things, my mom’s sisters waited patiently in Mami’s apartment for the men to arrive, prim, proper, and perhaps not entirely ready for the avalanche of men that would soon pour into the quiet building’s hallways. In a sense it was the event of all ages—all of Babi’s strapping bachelors and Mami’s giggly bridesmaids crammed into the narrow hallway of the seventh floor. I am surprised there aren’t stories of the neighbors getting involved in the day’s events too!

B: 嘩,周公子幾有型,靚唔靚仔啊?Babi個best man.

Wow, “Prince Chow” looked so cool. Isn’t he handsome? That’s your dad’s best man.

D: 你哋點解宜家刷緊牙嘅?

Why are you guys now brushing your teeth outside Mami’s house?

B: Your mother’s sister set us a lot of tasks, and we had to pass all these hurdles, these “exams,” before I could get to your mom. That’s Chinese custom. So my friends were there with me, playing these games.

Mami: 朗Wasabi,玩遊戲。

One of the games was that they all had to brush their teeth with wasabi to get inside the apartment.

B: 我哋食緊咩啊?

Wow, what are we even eating in this other game?

M: 唔知係雞蛋,定包。

Is that an egg or a piece of bread?

B: 嘩邊個諗㗎?呢啲遊戲。

Who even thought of these games?

M: 肯定我冇份玩㗎喇,呢啲。

I was definitely not involved in the planning of these.

B: 連你個婆婆都喺度玩!

But look, even your grandmother was playing!

B: 有一個 tradition, 就係娶新娘嗰啲姊妹問Babi攞利是。

Another tradition before I was allowed to meet your mother was for her bridesmaids to ask me for red packets.

M: 呢啲叫做 “開門” 利是。

These are called the “door opening” red packets.

B: 俾呢啲利是先可以開門,先可以娶新娘。

I was only allowed to marry your mother—to get in the door—after I gave her sisters these red packets.

B: 咁 Babi 而家俾咗呢啲姊妹嗰啲錢,佢哋一定會話係唔夠。

Look at the money I’m giving Mami’s bridesmaids now. They’re definitely going to say it’s not enough.

Meanwhile, my dad’s more relaxed family gathered in his living room, with 嫲嫲—Babi’s mother, and my paternal grandmother—in the middle. When I was younger, the nickname she gave was “狗啊,” or little dog.

Strangely, if there’s one thing that dates me, it is seeing how young Chan Lok-On and Geet-Geet, the two young relatives seen in this video. In my childhood, I had always thought that they were infinitely older than I was—and to see them so young, here, makes my imagined presence in these tapes feel more anachronistic than anything else.

D: 咁媽咪幾時嚟?

So is Mami ever going to come out?

B: 咪住先,仲要玩多啲遊戲,要跳呼拉圈,又要唱一首詩。

Wait, there’s still more games to play. I need to hula hoop, and then I also need to recite a poem.

And, finally, the grand moment. After hours of games, Babi was finally allowed in by Mami’s gatekeepers. To the doting applause of their friends, he finally picked her up from her childhood bedroom, where she sat nervously for the past hour, listening to ruckus going on outside.

But of course, the day couldn’t have been only pranks and games. Now that the bride had finally been located and the more friendly, communally-oriented games out of the way, there were also the more serious events that had to take place.

This included gathering with both of Babi’s and Mami’s families to go through the honorary customs. On the wedding day, my parents stressed to me how important it was to meet with elders and perform the proper rituals. So, as morning slipped into afternoon, Babi and Mami journeyed to each of their childhood homes, again, to greet their families and soon-to-be families—kneeling before their elders, pouring tea, and receiving gifts and blessings in return.

Of course, 婆婆—Mami’s mother, and my grandmother—couldn’t hold it together. And of course my dad, in another way, couldn’t hold himself together either, flashing a sneaky thumbs-up while my mother, the more sensible of the pair, whispered to my grandmother: “Don’t cry, or you won’t look good for the video!”

One final group photo with everyone finally gathered!

digression 2: finding home in “postmemory”?

What is the ultimate goal of this project?

In “‘We Would Not Have Come Without You’: Generations of Nostalgia,” Marianne Hirsch and Leo Spitzer introduce the notion of “postmemory.” Originally, the term described the relationship between the children of Holocaust survivors to their parents’ traumatic memories of oppression and disenfranchisement during the war (259). But the term can be generalized to encompass that “a secondary, belated memory mediated by stories, images, and behaviors among which she grew up, but which never added up to a complete picture or linear tale” (262)—to refer, in other words, to those stories passed around in confidence between family members.

In putting together this series of reflections, it has crossed my mind what, exactly, is the nature of this postmemorial project I am embarking on is—what exactly I am trying to do by tracing out these memories of my parents.

No doubt the most immediate objective of a postmemorial project like this one is to commemorate the story of my parents.

But, in a roundabout way, could it be that I am interested in postmemory as an affirmative act in myself? Could that be the ulterior meaning behind inserting myself, and figuring myself, within the memories of my parents?

Especially as a self-identified parachute kid—a child who has grown up split across countries due to his schooling—I wonder if a postmemorial longing signals a kind of fragility in my own identity and relationship to my heritage. As a student studying abroad for as long as he can remember, my (growing lack of a) connection to “home”—as a geography, as a mentality—continues to wear thin. In light of my understanding of my own belonging, am I using this project as a way to articulate—for myself, if anything—a connection to my own familial and cultural heritage?

Is this project an attempt at constructing a home for myself beyond the limiting spatiotemporality of my own circumstances and memory?

St. Anne’s Church

ST. ANNE’S CHURCH

Marital documents are signed during an hour-long church service at St. Anne’s Church.

Anna, my mom’s sister and my aunt

LATE AFTERNOON

The next stop of my parents’ wedding day, an hour-long church service, lasts in their memory as a sweetly comical interlude—no different in spirit, really, to the “door opening” games that preceded it. From the seriousness all in attendance—especially my dad’s rowdy brothers—attempted to put on, best as they could, to the fake attentiveness for a church service held in English, which most people in attendance barely spoke, much humor is submerged beneath the pristine exterior of these photos.

Lok-On and Geet-Jai, my godcousins

B: 我哋而家要去 church, 去 witnessing signing of the contracts, the marriage cert.

We’re now going to church to witness the marriage certifications.

B: 陳樂安同阿傑仔啦。

It’s your godcousins.

B: 哇呀,那么小的。

Wow, they’re so cute and young!

B: 你個妹先好笑。

[To Mami] Your sister (Anna) is the one who’s actually funny. (Because usually, she’s the least stern one of all of us—and here she is, the only time in life I’ve seen her wear a formal dress, like this one.)

B: 真係好後生呀啲人。

Wow, look at how young the people are.

B:你睇吓我個best man啲衫幾有型。Babi嗰套仲有型。你睇吓幾長。30年前,你睇吓幾靚。

Look at the suit on my best man. My own one was even more handsome. Look at how long it was. 30 years ago, it was so beautiful.

D: 你仲有頭髮。

You still had hair.

B: 梗係啦,成個張國榮㗎,大佬。

Well of course, I was a whole Leslie Cheung.

B: 嘩,我都唔認得我自己啊,咁後生。呢個頭呢,多得呀肥豬呀,阿肥豬幫我整㗎。

Wow, I didn’t even recognize myself for how young I was. I’m thankful for Fei-Zhu for helping me do it up.

Leslie himself!

B: 你睇吓呢個Father, 佢叫做 Father Russell。佢死咗㗎喇。

Look at this Father. His name was Father Russell. He’s passed away already.

M: 未, 佢未死㗎! 但係而家 St. Anne’s 嗰啲換晒啦。

No, he hasn’t! But St. Anne’s has changed all their priests, that’s true.

B: 我哋而家講緊嗰啲祝福說話,which我一句都聽唔到。嘩,幾眼瞓啊,嗰陣時, hahaha.

He’s now giving the blessings, of which I can’t hear a single word. Wow, at this point I was already so sleepy, hahaha.

D: 你而家眼瞓㗎?

You were sleepy here?

B: 我哋幾早起身㗎嗰日,大佬!

Well, of course, we woke up so early this morning!

D: Did you ever take a nap this day?

B: No,我哋直落㗎。為, Derek,結婚好攰㗎。When you get married, 你就會知道幾攰㗎喇,

No, Derek, we went straight from dawn to dusk. Getting married is tiring. When you get married, you’ll know how tiring it really is.

B: 你睇吓呀嫲嫲,好笑呀,佢完全唔知佢哋講緊咩㗎。而家因為佢哋講緊英文㗎嘛。

Look at your grandmother laughing along like it’s funny, even when the whole thing’s in English and she doesn’t speak the language! Haha!

B: 冇人識聽㗎嘛,根本就。

No one is listening at all, in all honesty.

D: 咁你點解要揀英文?

Then why did you choose English for the church service?

B: 威呀嘛!我哋嗰陣時搵嗰個 Father Russell 幫我哋搞㗎嘛。

Because it’s cool! And because we had gotten our local priest, Father Russell, to help us out, and he spoke English only.

B: 媽咪醒啊,帶咗件婚紗,佢而家一定瞓緊覺。你唔好話俾我聽你而家唔係瞓緊覺。

Your mother’s the smart one, wearing the veil. She’s definitely snoozing right now. [To Mami] Don’t tell me you aren’t sleeping right now in this frame.

D: Wah, Anna is so focused!

B: 哇,Anna一定唔聽入耳啦,坐喺度好似罰企。

Definitely not! She’s also zoning out, sitting here like she was just sent to stand the corner.

B: 你一陣間應該 focus on Winnie。你睇吓阿Winnie同嫲嫲几 focused?我肯定佢哋完全唔知而家講緊乜。

And you’ve also got to focus on Winnie later. Look at how Winnie and your grandmother are so focused? I’m so confident that they have no idea what’s going on.

B: 呀,契爺仲扮晒嘢添喎。

And, wow, your godfather is being so fake here too.

D: Well, then why does everyone look like they understand what is being said?

B: Because no one wants to act like they don’t understand!

An hour of church service begins…

People look awake, at least!

My grandmother looks so interested in the English pamphlet which she … doesn’t understand?

I wonder if I’d be awake if I were present…

I do think this smile from my godfather is genuine! :)

digression 3: irrealis mood and the question of permission

My parents’ memories are, in André Aciman’s phrasing, “not unreal” to me, even though I wasn’t there.

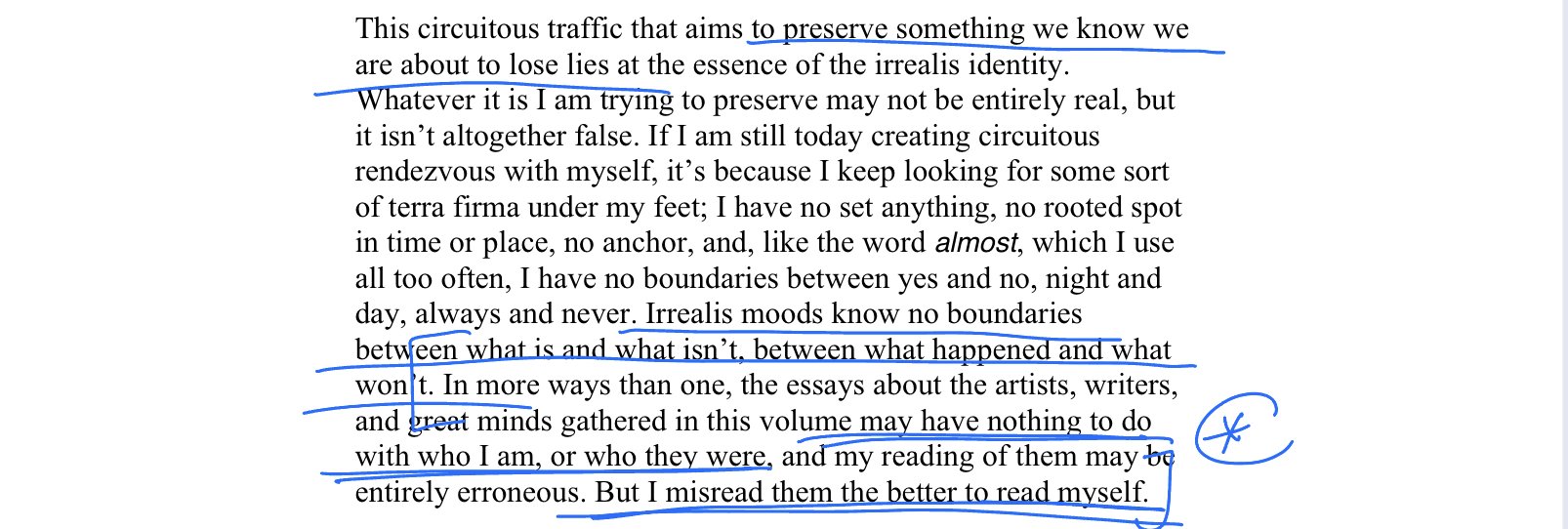

I cannot help but turn to André Aciman’s writing on nostalgia as I continue this project. He muses extensively on the themes of memory, loss, and identity, especially as they inform the complex emotions he harbors toward Alexandria—the city from which he was exiled as a child. I think constantly about what he must have felt on the eve of displacement from his childhood home, the departure whose significance he attempted describing to himself in these sentences:

Aciman’s memories are not confined within the limits of reality or time. Instead, Aciman describes his own emotions surrounding Alexandria—and, as it follows, his own identity—using a term he borrows from linguistics: the irrealis mood, or the irrealis identity. According to him, it is a state that “disrupts all verbal tense, moods, and aspects and seeks out a tense that does not conform to our sense of time.” His memories for his hometown, tinged with heavy nostalgia, extend beyond the confines of time into events that did not even actually happen to him. In other words, his emotions arise from even falsified or imagined memories.

I see value in his yearning because I, too, find credence in the irrealis state’s ability to determine one’s identity; it certainly explains the emotion I harbor toward the postmemory I grapple with, and the understanding in myself I derive from it. It feels liberating to know that I am not alone in deriving identity from memories that are not real, not mine—imagined sites that, in keeping with the irrealis state, “know no boundaries between what is and what isn’t, between what happened and what won’t.”

Is it relief that I am feeling? Certainly, it assuages some grain of doubt within me to know that it is, in fact, a valid interrogation that I am conducting between myself and these videos. To know that my thoughts about myself can involve the legacy of my parents, that they can be founded and rooted in memories I wasn’t directly involved in.

I don’t believe that Aciman is “entirely erroneous” in his embodiment of the irrealis mood in his own memory—just as I don’t believe that I am entirely in the wrong for reading a connection between myself and the wedding story of my parents. As Aciman suggests he may be doing in his own work, am I am embarking on this project all the more “to read myself”?

And if it is true that the “circuitous traffic”—that is, these thoughts I wrestle with—“… aims to preserve something we know we are about to lose,” then what, within myself, am I trying to guard against losing?

EVENING

BANQUET

The day’s festivities culminate in a grand serenade.

有了你 / Now That I Have You

歌词 / lyrics

有了你頓覺增加風趣 / Life with you suddenly feels more exhilarating

我每日每天都想見你 / I want to see you every day

哪懼風與雨 哪懼怕行雷 / Not afraid of wind and rain, of thunder

見少一秒都空虛 / I’m empty if I miss you for even a second

有了你頓覺輕鬆寫意 / Life with you suddenly feels relaxed

太快樂就跌一交都有趣 / So happy even tripping over is fun

心中想與你 變做鳥和魚 / I want to be with you in my heart, to become birds and fish

置身海闊天空裡 / in the endless sea and sky

My transcription and translation of his speech:

今日係1999年1月1號,呢一個日子,我呢一世都唔會忘記,因為喺今日,我得到我人生最大嘅光榮——我娶到Annie。

喜歡Annie並唔係因為佢嘅外表,或者佢個身型容貌,而係佢對我嗰份堅持、嗰份忠貞不二嘅情操,不離不棄。咁多年來,每當我遇到困難或者挫折嘅時候,佢都會喺我身邊,默默咁支持,鼓勵我。

除咗咁,佢都係一個非常之浪漫俏皮嘅人。同佢一齊,嗰種感覺,好似飲醉咗咁,好 high,好好 feel!

Annie:我愛你。

Today is January 1, 1999, a day I will never forget in my lifetime. Because today I’ve been granted the greatest honor of my life. Today, I am marrying Annie.

I love her not because of her appearance or physical attributes, but because of her persistent support in me, her unwavering loyalty to me, never leaving nor giving up on me. In all these years, whenever I run into difficulties or frustrations, she has always been by my side, silently supporting me and cheering me on.

Beyond this, she’s also such a playful romantic. When I’m with her, I feel under some kind of influence, a feeling beyond words!

Annie—I love you.

Then, the night continues…

If there is one most important story—the story that has been passed around the dinner table so much over the years, the story that still makes my parents laugh if it is brought up, the story that even occasions my mother to pull out the score and begin playing a few verses on the piano at home—it is this:

A banquet hall in darkness, lit up suddenly by a single beam of light on my father. In a white tuxedo, he makes his way to front of the banquet hall, holding a microphone. He sings "有了你” (“Now That I Have You”), to the loving whoops and cheers and flowers of his friends, to flowers thrown on him by his niece and nephew. He gives a speech about his love for my mother, so smooth and soppy it feels indeed like he is a celebrity in his own right.

When he finally reaches the front of the room, the curtain is drawn back, and it is revealed, all along, that it was my mother who was playing the piano in the background.

afterword

hooks was right in telling us that photos allow us a way into seeing ourselves (62). Having put this project together, I know now that these images—mediated to me in the postmemory of my parents, inscribed here as they are alongside my own thoughts—don’t just mean something to me. They also say something about me.

What exactly, I choose to leave open. But there is something, I know, in the enactment of essayism in understanding the relationship between me and my parents. Perhaps it is something to do with the act of creation itself—of the time and effort spent in putting together these memories. In the act of assembling this page—watching these videos, soliciting the commentary of my parents, sitting with their music—I have, in a way, placed myself into their history.

And I have intensified my own knowledge of and relationship toward every element I have witnessed within these videos: not only my relatives and the places in which I see them, but the emotions that accompany them. The way Anna, or my godfather, or my grandmother(s) smiled in church, pretending they were listening. The way Ah-Keung and Ah-Kei cheered for my father’s proud walk on the same path I used to wait for my schoolbus. I have accessed a time before myself and learned more about myself—the people and places I know myself, and how they relate to the postmemory I am inheriting—in this reflective process.

In the end, I am thankful to my parents for supporting me throughout this project. I have always admired them for that: Reasonable, established adults into middle-age as they are, they are, and always have been, game to entertaining new ideas, such as throwing the city’s biggest party on New Year’s Day in 1999, or sitting with their son who wanted to look back on this day 24 years after the fact, because he was curious to pursue this as a project of his own.

In a way I have always regretted that I never had the chance to be with my parents, and all their friends and all our family, on this most special day of theirs. Still I long to have been there with them, celebrating them on their special day—even if I know such a fantasy is, of course, illogical and impossible.

But, in another way, part of me understands that, for all it matters to me, I have been there with them all along.